INTRO

Welcome to Business in Great Waters. I’m Jen Holmgren.

Growing up in Massachusetts, I grew up with the fight taken up by indigenous people and allies for equality and recognition. In advance of Gloucester’s 400th anniversary, I will do my best to stay away from whitewashing or sugarcoating our past. Before Samuel de Champlain and John Smith put Cape Ann on the map (by literally putting it on a map), there were thousands of Native Americans here. They were killed off by pestilence or violence. As I retell this history recorded by white Europeans, I understand it is just that. A history written through the colonizer’s lens.

To back these words up with actions, I encourage all listeners to visit the Massachusetts Center for Native American Awareness website. The MCNAA was founded in 1989. Its headquarters are in Danvers, Massachusetts. They write, “Our mission is to preserve Native American cultural traditions; to assist Native American residents with basic needs and educational expenses; to advance public knowledge and understanding that helps dispel inaccurate information about Native Americans; and to work towards racial equality by addressing inequities across the region.” I’ll leave a link to the website in the show notes. Please consider making a donation, or getting involved.

And thank you for bearing with me – I am not an historian by training. I’m a Registered Nurse with a communications degree, and I love Gloucester and America with all my heart. A single podcast episode has a linear structure, but my hope is to explore the dimensions of Cape Ann historical narratives as a whole over the course of this series. I hope you enjoy it.

One more brief recommendation: try to get your hands on a copy of the book Gloucester, Massachusetts Historical Timeline, 1000-1999, compiled by Mary Ray and edited by Sarah V. Dunlap with assistance from the Gloucester Archives Committee. There have been so many indispensable and unique books published about Gloucester and Cape Ann. I have found the Timeline, lovingly researched and compiled, has so many leads and quirky stories it’ll keep the most information-hungry history buffs entertained for ages.

Let’s dive in.

***************

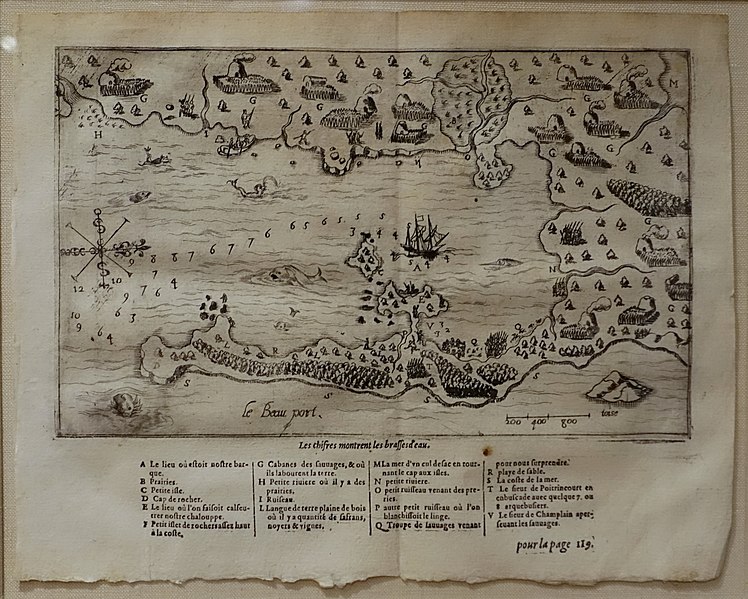

Gloucester’s modern colonization and settlement began in 1606 when famed French explorer and colonizer Samuel de Champlain came upon Cape Ann. Champlain was acting under King Henry the Fourth’s orders to establish a permanent French colony. While ultimately Champlain would settle farther north, he was taken with Cape Ann, naming it “Le Beau Port,” or “The Beautiful Harbor.”

Recognizing the value in claiming this part of the North American continent, England began planning in earnest to establish settlements in Massachusetts. Captain John Smith, who gave New England its name, also explored Cape Ann’s coastline in his travels. He caught sight of three islands off Sandy Bay (now Rockport) and named them the three Turk’s Heads. These islands are Straitsmouth, Thatcher’s, and Milk Island. Turkey must have made a huge impression on him, because he named the Cape itself “Tragabigzanda” after a woman he’d met in Istanbul while a prisoner of war. English royalty approved of the New England Name, but Prince Charles decided to rename Tragabigzanda “Cape Anne” in honor of his mother, Queen Anne.

But what of the natives of Cape Ann, the Agawam tribe of the Algonquin people? At the time of European settlement, the Sagamore, or Chief, of the Agawam tribe was Masconomet.

I’m going to read some excerpts from Historic Ipswich’s 2021 article, “The Bones of Masconomet,” for the best information. I’ll link the article in the show notes. I highly recommend the Historic Ipswich blog for more information about Cape Ann’s neighbor to the North.

“When English settlers arrived at what was then known by the local Indians as Agawam, most of the tribe had already died from a plague brought by contact with Europeans. [As an aside, In my research, I have found it was assumed to be smallpox, and it was about 20 years before the following events, or sometime in the 1610’s.]

“On June 8, 1638 the last Sagamore (chief) of Agawam, Masconomet Quinakonant signed over all the land under his control to John Winthrop Jr., representative of the English settlers of Ipswich. The deed read as follows:

“I Masconomet, Sagamore of Agawam, do by these presents acknowledge to have received of Mr. John Winthrop the sum of £20, in full satisfaction of all the right, property, and claim I have, or ought to have, unto all the land, lying and being in the Bay of Agawam, alias Ipswich, being so called now by the English, as well as such land, as I formerly reserved unto my own use at Chebacco, as also all other land, belonging to me in these parts, Mr. Dummer’s farm excepted only;

“And I hereby relinquish all the right and interest I have unto all the havens, rivers, creeks, islands, huntings, and fishings, with all the woods, swamps, timber, and whatever else is, or may be, in or upon the said ground to me belonging: and I do hereby acknowledge to have received full satisfaction from the said John Winthrop for all former agreements, touching the premises and parts of them; and I do hereby bind myself to make good the aforesaid bargain and sale unto the said John Winthrop, his heirs and assigns for ever, and to secure him against the title and claim of all other Indians and natives whatsoever.

“Witness my hand, Masconomet, 8th of June, 1638.

“…Masconomet ruled all the tribal land from Cape Ann to the Merrimack River, which he sold to John Winthrop and the settlers of Ipswich for a sum of £20. The Sagamore died on March 6, 1658 and was buried along with his gun, tomahawk and other items on Sagamore Hill, formerly in the Hamlet section of Ipswich and now within the town of Hamilton. His wife is buried alongside him.

“On March 6, 1659 a young man named Robert Cross dug up the remains of the chief and carried his skull on a pole through Ipswich streets, an act for which Cross was imprisoned, sent to the stocks, then returned to prison until a fine was paid. He also had to rebury the skull and bones and build a two-foot-high pile of stones over the grave. His accomplice John Andrews was instructed to help and make a public acknowledgement of his wrongdoing.

“In Native American tradition the spirit of a person is called back when his grave is desecrated, and must roam the Earth looking for his bones. After the bones are found, a proper burial ceremony must be performed by his people before he can rest.

“In 1910, a stone was inscribed to mark the grave, and in 1971, a memorial service was held and a larger stone monument was erected, but it was not until 1993 that a ceremony with Native American rituals was conducted. After 355 years, Masconomet’s spirit was finally at peace. The final resting place of Masconomet is accessed by a paved road leading past the Sagamore Hill Solar Radar Observatory, and is graced with tokens of reverence.”

The first permanent settlement of the Massachusetts Bay Colony was established in 1623 at Fishermen’s Field, now known as Stage Fort Park, Cape Ann.

The reason it’s named “Stage Fort” is not absolutely concrete, at least the “stage” part. It’s likely because, in the 1600s, colonists used this large area of land abutting the harbor as a place to set up wooden stages to dry and preserve fish. The Fort part came a little later. If you come to visit, you can still see a grassy battlement with lovingly restored cannons, used in the Civil War, facing the Harbor. It was a working fort during conflict and in peacetime, from 1625 through the Spanish American War in 1898.

Although Gloucester was originally settled in 1623 as a fishing village, its residents decided to move a little further south to Salem, Massachusetts shortly afterward because it was not profitable. They came and went, mostly men working in the fishing and lumber industries, but they didn’t return here in numbers great enough to establish a town until 1642. At that time, the King of England allowed the settlers a grant, and the First Parish Church was established on Beacon Hill in what is now part of Downtown Gloucester.

Salem, MA, founded by Roger Conant and known in the colonial days as Naumkeag (named after the nearby indigenous Naumkeag village) was a bigger hub for trade and business than Boston was during the colonial times. Once fully established, Gloucester’s fishing and timber industries prospered while Salem, just 14 miles south by sail, enjoyed its time as the most influential city in Eastern Massachusetts.

Between 1640 and 1650, a total of 82 settlers came to Gloucester. A couple of the more locally-famous of these were Reverend Richard Blynman and midwife Isabel Babson.

If you’re familiar with Gloucester, you are undoubtedly acquainted with Stacy Boulevard, though that was built far after the colonial times. More than that, you know about the Blynman drawbridge, or the “Cut Bridge,” which splits the Boulevard roughly down the middle. The Blynman Bridge is named for Reverend Richard Blynman, from Marshfield, MA.

Cape Ann residents asked Reverend Blynman to come to Gloucester to lead the First Parish church in the 1640s. Blynman settled here with other parishioners from Plymouth County.

At this time, all Gloucester residents were obligated to attend church at the Meeting House on the Green, including the residents in West Gloucester. If this rule was violated, a resident could be prosecuted as a criminal. For example, John Kettle, a minor, was brought before Salem Court for breach of the Sabbath and for stealing.

The journey to the meetinghouse could be time-consuming and arduous. Those West Gloucester residents who did not live near the natural land bridge abutting Gloucester Harbor would have to take a ferry across the Annisquam River to reach the meetinghouse. That changed a few decades later, and I’ll do an episode on that.

Reverend Blynman was permited to dig a ditch connecting Gloucester Harbor to the Annisquam River, where he was granted land, in 1643. The town was given free rite of passage over the newly-installed bridge at “The Cut”, as it is still known. According to Babson’s History of Gloucester, published in 1860, Blynman was to “cut the beach through, and to maintain it, and to have the benefit of it to himself and his for ever, giving the inhabitants of the town free passage.” Blynman was obligated to maintain the bridge and the cut. As a reverend, he was not a popular man, though as a person, his parishioners and fellow townspeople were fond of him. He was pretty much run out of town sometime between 1649 and 1650 and, along with 13 other families, resettled in New London, Ct. Because of lack of financial resources, the town of Gloucester was without a minister until 1661. At that time, Reverend John Emerson was hired and a new meetinghouse was built roughly where Gloucester’s Grant Circle Rotary is now.

Because American colonial history is so intertwined with Puritan and Protestant histories, I will explore more in-depth figures such as John Murray, the founder of the First Universalist Church in America, at a later time.

Isabel Babson was a far more popular figure whose legacy lives on Cape Ann to this day. Please be warned: the following paragraph details a brief description of violence and miscarriage.

According to the Babson Historical Association, “Isabel Babson, when she arrived in Salem from Somersetshire in the southwest of England in 1637, was around 60 years old (no birth record exists to verify her birthdate). It is safe to assume that she was by that time a seasoned, expert midwife, who very likely trained younger women in the practice. Religiously, there was expectation that Puritan women as young as their mid-teens would be preparing for a fertile motherly career. This entailed the need for midwives. Good midwives were scarce in the colonies at that early time, and so Isabel Babson likely played an important role in her community in Gloucester. For this reason she was brought in as an “expert witness”, so to speak, (at the age of “about 80” in her own words) regarding a 1657 trial against a local man who was accused of causing a woman to miscarry a late pregnancy and almost lose her own life in the process. Isabel’s sworn deposition attested to the good character of the expectant mother, who had been accused of witchcraft, and described the brutal experience of childbirth that resulted in the death of the fetus and the severe trauma of the mother. “Mother Babson”, as she is referred to in the deposition, must have had a good reputation, such that an accusation of witchcraft would not touch her, as midwives were often accused of being witches themselves. Midwives were expert in preventing commonly fatal complications of childbirth, and Isabel’s description of how she and her team kept the mother alive attested to this expertise. Contrary to the Enlightenment expectation that midwives plied their trade as enchanted alchemists, they were in fact one of the most reliable and effective medical practitioners of early colonial New England. The best midwives could boast a successful record of thousands of healthy births and only a handful of injuries or deaths, even in such early modern times. It is no surprise that midwives were regarded as local leaders and legal authorities.”

If you come to visit Gloucester, be sure to check out the Isabel Babson Memorial Library on Main Street. It is dedicated to Isabel Babson’s memory and devoted to the topics of parenthood, maternity, and lifelong health and caregiving. I’ll include information about it in the show notes.

Where did Cape Ann’s settlers make their homes, though? For many, the interior of the island, an area known now as Dogtown, was where the oldest established settlement was built. There was readily-available fresh water thanks to springs. It was away from the harbor, which meant pirate attacks were less likely. And it was near the First Parish, the hub of the community. If you visit, stop by the Cape Ann Museum and buy a map of Dogtown. Make sure you bring your snacks, hiking boots, bug spray, and plenty of time. Don’t go alone; it’s easy to get lost. But treasures there include the famous Babson boulders along with numerous cellar foundations belonging to some of Gloucester’s true characters from antiquity. I’ll devote a whole episode to Dogtown, but for now, it’s time for me to sign off.

Please visit the BGW blog, bgreatwaters.com, for a transcript, pictures, and more info. That’s the letter b, then great waters, all one word.

If you feel so moved, please head over to my Patreon page: www.patreon.com/bgw. There you’ll find special perks for monthly supporters including merch. If you aren’t able to sign up for a Patreon at this time but would like to support BGW, please tell your family and friends about us, and if you can, leave a review in your podcast app. Reviews boost visibility for BGW, or really any other podcast you listen to, and us creators really appreciate it because it helps us bring you more content.

Thank you for listening, and thank you for your support.

Books:

History of the Town of Gloucester, Cape Ann, including the Town of Rockport: John J. Babson, c. 1860; republished 1972.

Gloucester, Massachusetts Historical Timeline: 1000 – 1999, compiled by Mary Ray, edited by Sarah V. Dunlap, assisted by Gloucester Archives Committee: Priscilla Anderson, Ann Banks, Stephanie Buck, Kathleen Cafasso, Lois Hamilton, Priscilla Kippen-Smith, Myron Markel, John Quinn, Alan Ray, Elaine Smogard, Janie Walsh, Natalie Whitmarsh. c. 2002, Mary Ray.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chief_Masconomet

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Massachusetts_Bay_Colony